1969.

Just passing out from school, I had my first article published in The Junior Statesman (still not renamed JS) in their section, ‘Focus’ — which ran an interview with a celebrity. The next week there was an interview with one Shyam Benegal, if I remember, by a journalist called Bawa. Going through that interview I first got the feeling that there was something odd going on here. How could the publication repeatedly make an error? Spelling mistake. Bengal. Not Benegal. But then, you can’t have a surname called Bengal! India is a country of many castes and cultures and perhaps some people, who are originally from Bengal, who settled elsewhere, perhaps carried the linkage of their home state!

Turned out, it was not so wild. Many Tamil surnames have the name of their place of birth. There was one Mr Calcutta Jagannathan who was on the Board of ITC. The leading political family in Tamil Nadu have a Stalin, a Bose and even a Nehru!

Soon it sunk in that it was indeed a Benegal and he was from advertising, made ad films, short films, and documentaries. In 1974, Benegal’s first feature Ankur hit the screen with a newcomer, FTII-trained Shabana Azmi, whose acceptance in Kolkata was very high — Kaifi saheb-er meye (Kaifi Azmi’s daughter). Kaifi Azmi was a Marxist hero, who had once taken refuge in Debabrata Biswas’ house when the Communist Party was banned, and in 1971, one of his poems, “Main koi lakeer nahi hoon ki mita dogey mujhey” was most inspiring in the context of the Bangladesh movement.

By then I was totally immersed into the world of Kolkata Culture, and the Editor of Kino, the journal published by the Cine Club of Calcutta — of which I had become a member — asked me to do a review on Ankur. I was nervous. I had published interviews with film starts and related stuff — but a film review? I took my chances and my first review, “Ankur: A Poem of Protest” was published. By the time I joined advertising, I heard more about Benegal’s documentaries, especially Pulsating Giant being treated like a benchmark on industrial films. Years later I joined Advertising & Sales Promotion Co (ASP), where Shyam had worked as the head of films, his assistant being Prahlad Kakkar. I would love to take a peek at the ad films he had made while working for ad agencies.

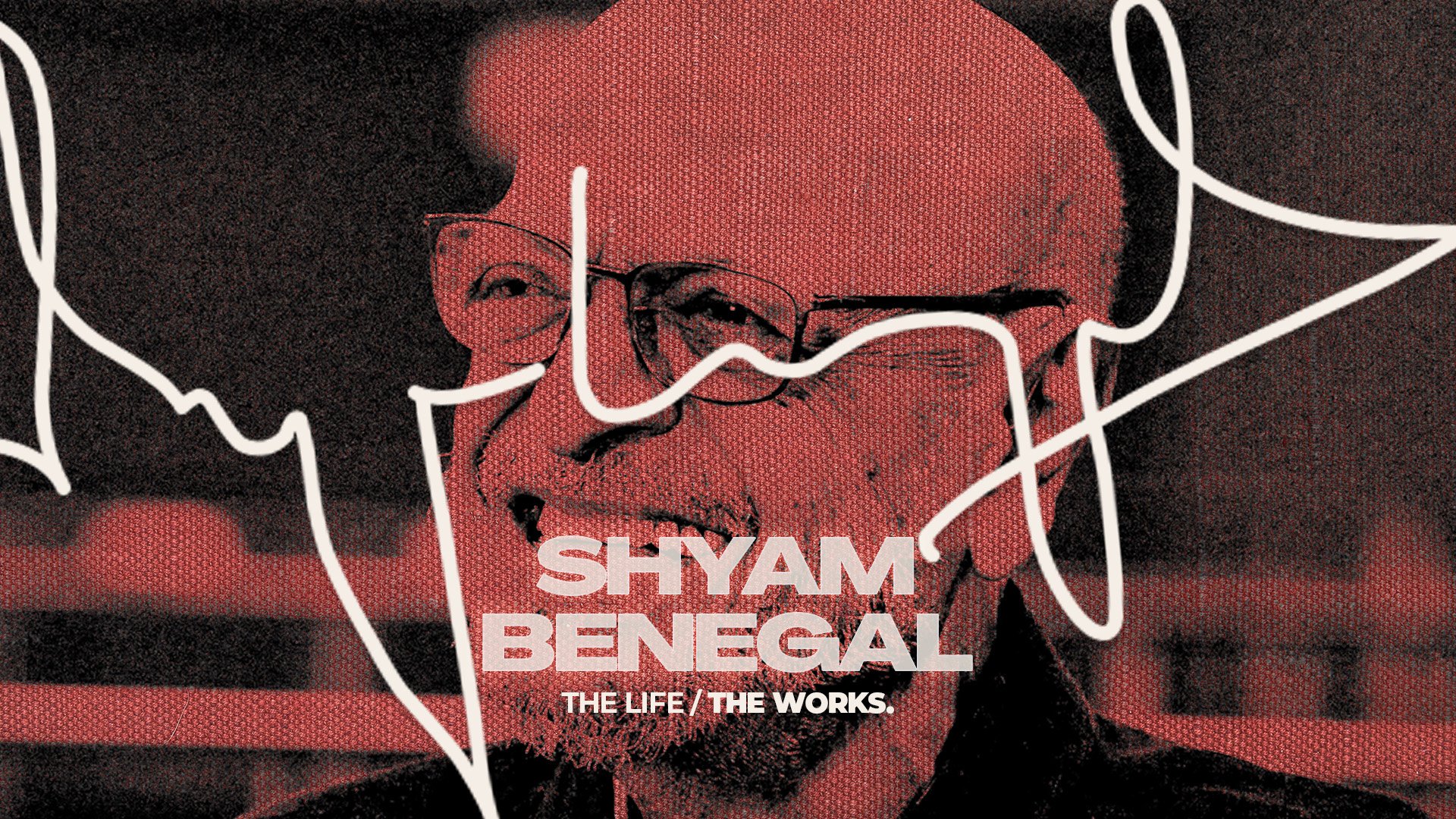

Post Ankur, Benegal symbolised good cinema, good storytelling — and I must add, good music. While we had our Ray, Ghatak, Sen, Sinha, Benegal was leading the pack from Mumbai and through the seventees had produced a good number of parallel cinema. While the number of films by Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, and others were limited, Benegal kept delivering at regular intervals. Be it Trikaal (one of my favourites), or Mammo, or Susman — and even the television series, Bharat Ek Khoj — all of them were clean, neat, well-made films and he regularly introduced fresh faces.

‘The Complete Works of Shyam Benegal’ will remain a process of learning for years to come.

Kahaani Koncerti is privileged to put together a series of articles and opinions on Shyam Benegal and we would like to thank our contributors whom we pestered — but all of them complied with a smile. We are fortunate to have such friends. We hope you will like them and we look forward to your comments and continued support to our platform.

Sujit Sanyal | Editor-in-Chief, Kahaani Koncerti

Srabanee Chakrabarty met Usha Uthup, our Usha di, to talk about her association with Shyam Benegal. We are indeed grateful to Usha di for talking to us and telling us about the iconic Vande Mataram she sang for The Making of the Mahatma.

Exclusive to Kahaani Koncerti.